Madhu was busy when he heard his father call him

“Go bring fetch some pushkaramoolam,” Madhu’s father ordered without taking his eyes off the newspaper. The boy stopped chopping the herbs and looked at his father, engrossed in his daily intake of news. “Achcha (father), the customer will come any moment now. I still need some time to complete the yogam,” he said, suddenly becoming aware that he raised his voice a little. In answer, two eyes appeared above the newspaper, telling him in a clear language that his task, as of then, was to obey.

Madhu didn’t meet his eyes.He hurriedly put down the madaal (an upward curving billhook used to chop up dried herbs and roots) and washed his hands. From behind the fat tamarind log on which he did his work, Madhu took a small gunny bag and a length of coir and walked out of the shop,aware that his father’s eyes had not left him.

His took his old cycle, rested against a steel pole near the fruit seller’s stall, and began to push it. It was around 5 ‘o’ clock in the evening.Madhu looked up and squinted at the Sun. For a second before he looked away, he could make out its outline. “Don’t set before I come back,” he whispered as he took the right turn and started down the dilapidated road leading to his family home five kilometres away. The cut on his right index finger throbbed as he gripped the cycle’s handle.

“Going to steal again, little boy,” an autorickshaw driver jeered as he passed their stand. Madhu didn’t lift his head. He put his left feet on the pedal and gave the cycle a couple of quick thrusts with his right leg. As soon as he felt the cycle gathering speed, he hopped on to the seat. The descent brought him a gentle breeze that made him forget the insult. Madhu’s father is the local vaidyan and he was often asked to collect herbs from thickets on roadsides. While his father had always told him to not enter other’s people compounds to collect herbs without their permission, Madhu often did. He had been caught several times but was let off for the sake of his father. Over time, however, he earned himself the unpleasant epithet of ‘thief.’

It was a Saturday and Madhu knew that most of his cousins would have gathered at their family home to spend the night talking, playing and listening to his old aunt’s stories. ‘Maybe, achchanwould let me go as well if I finish the work early. I can still make it before ammayi (aunt) begins her stories,” he mused as he started pedaling the cycle. In his heart, however, Madhu smothered the bitter fact that none of his kin wants him near them. They said he was the carrier of the family curse; an evil spell cast on his ancestors centuries ago. Madhu pedaled faster, the steady creaking of his rusting cycle timed his heaves like a metronome. His cycle shot through the narrow road flanked on either side by lush vegetation and towering trees;not many lived along this path, which ended at the foothill.

Mustering courage

He hesitated a little before entering the premises of his ancestral home

At a quarter to 6, Madhu reached the run-down compound wall of his old tharavad (family home). He got down from his cycle and rested it against the old tamarind tree that had replaced the long-gone kazhala (a kind of wooden gate). In the waning light, the tree looked like a giant gargoyle. Madhu often avoided coming to this place. He had heard that the old tharavad was destroyed in a massive fire over a century ago and the entire family replanted itself to another location five kilometres away; a great distance in the olden days. None wanted that land even when the properties were partitioned decades later; none visited it; none owned it.

That day, however, Madhu mustered all his courage to go to the woods; he knew that it was a treasure trove of rare herbs and, somewhere in its thickets he might find the herb he was looking for. The boy hurriedly descended the flight of stone steps that once led to the yard of the bygone mud building. “I will just go over there, find it and run back; it would not take much time,” he assured himself, aware that his heart was pacing faster.

Madhu had heard the story and the memories of it made him shudder. They said it happened during an age when there was no death because Shiva had killed the lord of death himself – Kaalan. The sick and the old did not die.They continued to live even when their bodies started to disintegrate. Over time, their spines buckled, and they started walking on all fours. It was said that they eventually metamorphosed into something that looked much like a large frog that leaped around begging their younger kin for food; words came out of their toothless mouths in an incomprehensive gibberish.

Then came the famine; it was so devastating that families sold their sons and daughters for a handful of paddy. Hunger drove men and women into doing the unthinkable and the most heinous of acts. The undying were thrown out of the houses; some were killed by their own kin, who were unable to feed themselves.Starving but unable to die, the undying grovelled near the numerous kaavu dotting the village in those times. It was on a moonless night of that dark era that the curse fell on a newlywed couple.

Something lurks in the darkness

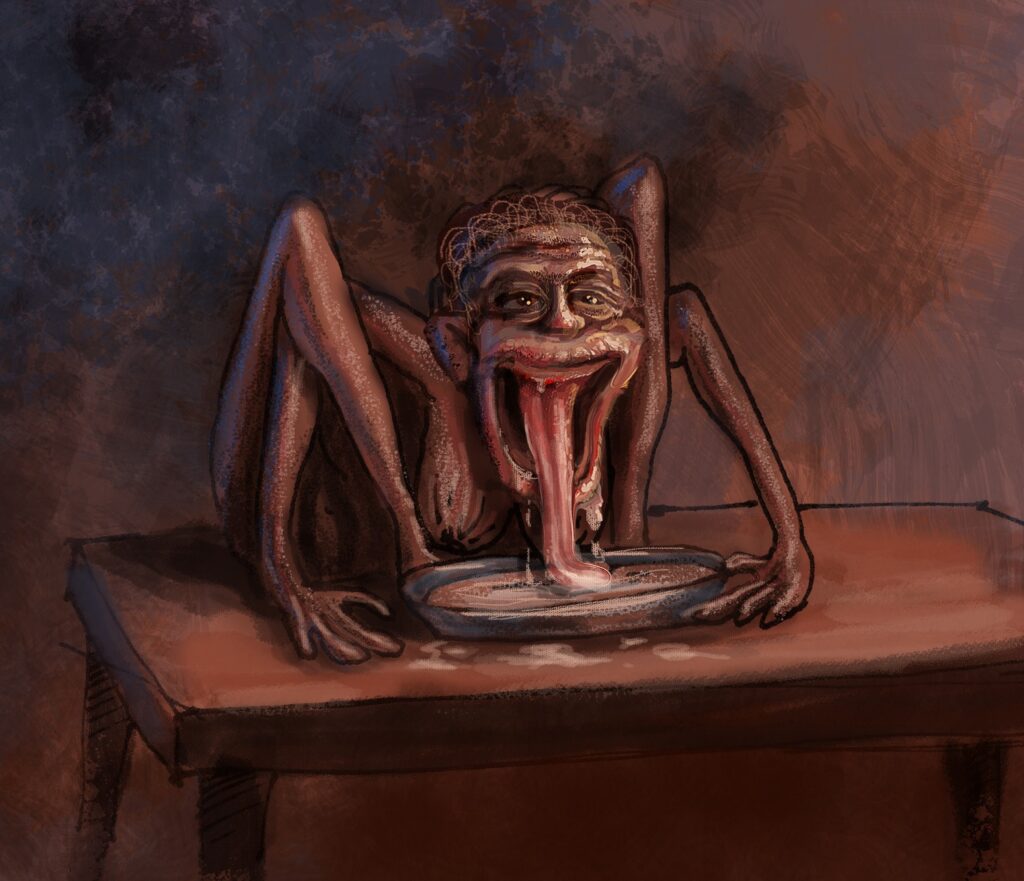

The abomination made a nauseating sound as it worked its throat swallowing the baby

A fire broke out at a house nearby and the woman’s husband and her father-in-law rushed out to help that family put it out. Heavily pregnant, the woman waited with bated breath for her husband’s return. Around midnight, while the men were still away, the woman’s water broke. Holding her bulging belly, she slowly sank to the floor where a grass mat had been spread. An oil lamp burned nearby, casting a little circle of light around her.

In the throes of childbirth, she, a frail woman, writhed as the contractions began. She felt her cervix dilate and the baby’s head moving into the birth canal. She prayed to all gods to keep her conscious and not let her faint. Beads of sweat formed on her forehead and rolled down her sides, soaking the bundle of clothes she used a pillow. She counted the moments, hoping that her husband would come back any moment, and that was what she thought when she heard the door being pushed open.

A gust of cool air gushed into the house. She cried out her husband name asking his help, but no reply came. “I am here. Come quickly,” she shouted and waited for those familiar footsteps to approach her. Instead, she heard something strange – plops. They were irregular, often separated by several seconds. Even as her pain intensified as the baby crowned, she heard that strange sound coming closer. The flame of the oil lamp flickered, making shadows dance on the walls of that small room. Her eyes ached, but even as overpowering exhaustion beat her down, she felt a presence in thick darkness across the room. That plop came from just a few feet away.

Her head, sweating profusely, fell back on to the wet pillow. Taking another deep breath, she pushed again and again until the baby’s head came out, but before she could push again, she felt something grab the head of the baby. She screamed in excruciating pain when, in violent jerk, the baby was pulled out of her. Horrorstruck, she lifted herself on elbows and started between her parted legs. What she saw made her head go numb.

Sitting between her legs was a crone so abominable that its mere presence in that place of new life made the woman retch. She could see only the back of its head as it licked the floor slick with birth fluids. From its shining head, a few strands of worn white hair stood out like the branches of a dead tree. In next instant, however, an alarm coursed through her body – her baby; where is her baby? Disgusted and terrified at the same time, she managed a feeble kick on the head of that horrible creature whose cold breaths licked her inner thighs. Uttering a squawk, it staggered backward and lifted its head, revealing its morbid face in full. It was then that she noticed something that pushed her into an abyss of insanity. Pocking out of its bloody toothless mouth was the tiny hand of her newborn. In between that nauseating sound of flesh getting crunched between toothless gum, she heard it say, “Ka..nji …. kanji (food).”

An unexpected find

The sunlight was waning fast; Madhu wanted to get out of the premises as soon as possible

“You just don’t find it when you really need it,” Madhu cursed under his breath as he waded through the thickets in search for the medicine. Koduthoova, that plant covered in microscopic needles and growing abundantly in the coppice, made his task all the more difficult. His hands and legs ached and itched wherever the plants touched. Little by little, Madhu got closer to the southern end of the compound where the undergrowth thick. As twilight descended on the landscape, Madhu finally found what he was looking for.

Under the remains of the old compound wall was a large cluster of the herb; its small white flowers spread a fragrance that Madhu found utterly at odds with the pungent odour of decay arising from the undergrowth. He crouched near the plant and, using the small handle-less pick-axe that he always carried on his cycle, began digging for its butter-white roots. The plant was big, decades or may be a century old. “If I could dig deep enough, I might get enough to last a whole summer,” he said to himself.

At long last, Madhu found a fat root going deep into the ground. He tried to pull it out, but it refused to break. He stood up, his entire body covered in sweat and his back aching. As he wiped the sweat off his forehead with the back of his hand, Madhu looked around, baffled by the eerie silence so deep in the woods. Holding one end of the pick-axe with both his hand, Madhu raised it well above his head and brought it down hard onto the root, sever it. However, the teeth of the pick-axe sank into the soil and hit something hard, something hollow and metallic. Madhu froze. He put the pick-axe down and stood up, breathing heavily and staring at the pit he made. ‘Had I found it?’ a question rose in his head.

Retribution

Seething with anger, the men didn’t hear the pleas of the creature

When the woman’s husband finally returned home, he found the crone licking clean the birth fluids from the floor and the woman lying unconscious nearby. It is said he uttered a heart-wrenching cry when he realised what had taken place. Red with rage, he rushed to the cattle shed and took a long length of rope. He made a noose and put it around the hag’s neck. He hauled it out of the house and dragged it through the thickets. The man’s father, equally overcome with rage and horror, had prepared a pit near the southern wall. He had bought a large pdav (a huge earthen urn with a bulging belly and a narrow neck used in the olden days to ferment Ayurveda preparations). The two men then bludgeoned the crone with firewood and pushed its broken body into the urn. It is said that the crone, the great-great grandmother of the woman, kept asking them to stop and show mercy and that it was starving, but nothing could stop the husband, crying his heart out for the gruesome fate that had befallen his firstborn. The men sealed the pdav’s mouth with a brass plate, tied it firmly coir and buried it. Muffled screams were still being heard when the men filled the pit. When the men stood on the grave packing the soil over it with their feet, they were said to have heard the crone uttering, in its most evil voice, a terrible curse.

The curse

He looked inside the urn, half expecting something alive in it

Madhu waited for a few minutes, unsure of what to do. He was curious to see if he had indeed stumbled upon the grave of the undying. He sat on his haunches and carefully removed the soil he had loosened until his fingers touched on what felt like something smooth. It was a brass plate. Patina covered its top but something – letters in an undistinguishable language – rose over it like letterpress. Madhu kept removing the soil until the full plate became visible in the dim blue light that tickled in through the canopy. He tapped on it with his knuckles and waited, but nothing came out of it. He wedged the teeth of the pick-axe beneath the plate’s edge and pressed on the other end. When he could not do it with his hands, Madhu stood up and used his feet. The plate budged and rose a little.

Madhu, excited to see what was inside the urn, sat on his haunches and removed the plate. He peered inside, with his face inches away from the urn’s mouth. He smelled old dust and rust. There was total darkness inside it. Several moments passed; Madhu held his breath; the pounding of his heart reverberated in his ears, but he neither heard nor saw anything. After what felt like a couple of minutes, Madhu gave up, suddenly realizing that he had taken too much time. He grabbed the gunny bag and the pick-axe and hurried back to his cycle, but he planned to come back tomorrow, with a torch.

It was half past six when he got back to the shop. His father was fuming with anger and Madhu fumbled for an explanation for his delay, finally settling on a punctured tire. As he worked under the hot incandescent bulb for the rest of the evening, Madhu’s mind was full of anticipation of what he might find inside the urn tomorrow. He giggled inaudibly thinking how all his cousins and brothers might react when he would finally tell them about his find. “Will they believe me? Of course they will! I will have proof,” he told himself.

It was a particularly busy day and Madhu’s father told him to clean and lock the shop before leaving for home around 11 pm. By the time he finished the chores, it was already a quarter to 12. Closing that old shop was a task Madhu detested. It was an old shop, just like most shops in that town. Steel shutters were still a novelty and most shops had the old-fashioned nirapalaka in which long wooden planks are slid along wooden channels. It was when he started sliding the planks that he noticed his fingers; the bandage he had put on had come undone and the open wound snarled at him.

By the time he reached home, all had gone to sleep. He used his spare key to open the door and entered the house. A single candle cast a circle of dim light around the kitchen table, on which lay his food—kanji (rice porridge) and an omelette. Madhu put down the small bag he was carrying, washed his hands and started having his supper. He was so hungry that he drank kanji in large gulps. What he had forgotten to do was to close the door.

Coming undone

Manu’s mind was fast descending into a chaos

Madhu looked at the flickering candle flame as he ate — his mind was blank, his body tired. The only sound inside that house was of the steel spoon scooping the porridge. From the corridor between the verandah and the kitchen, however, another sound arose suddenly. Madhu stopped eating and listened. ‘Plop,’ camethe sound, this time closer. Madhu’s hair stood on their ends when he suddenly remembered that he had not closed the door. He scrambled to his feet and looked at the darkness that thickened beyond the kitchen. He wanted to go and close the door but dread had paralysed him. The sound kept coming closer, the last one coming from a few feet from where he stood. Madhu backed away.In the dark recess of his conscious self, he understood what he was about to witness.

With quickening breaths, Madhu watched in horror as two withered and wrinkled hands protruded from the darkness and felt the floor as if whatever those hands belonged to were looking for something. Madhu stopped hearing the clock’s ticking; instead, he heard a croaking voice:“Kanji… kanji venam, (FOOD, WANT FOOD).”Terror gripped his entire being when Madhu saw that apparition jumping onto the kitchen table, baring its withered and wretched form to Madhu’s bulging eyes. Hardly bigger than a dog, it was completely naked; its skin flaked off as it started devouring the remaining food on the plate. Petrified, Madhu looked on even as that ancient being lifted its head up and stared at him. He believed he saw an ugly grin spreading on its repulsive face, “Ammammayk kanji thaa kutta!(give some food to your grandmother, little boy!),” it croonedas it licked clean its upper lip with a long white tongue.

Madhu found himself smiling at it. With growing terror he found himself walking towards it. In his right hand he saw pick-axe. Screaming, he struggled to control himself. No sound, however, came out of his mouth, which had by then mutated into an ugly grin. He saw the things form more clearly as he approached it. Crouching like a frog, it kept grinning at him with its toothless mouth. He could not see its eyes. They were so deep set that both sockets looked globs of solidified darkness.

Laughing and muttering doggerel, Madhu raised the pick-axe above its head. When he brought down its sharp point atop its bald head, Madhu heard himself scream. Possessed, he kept stabbing that thing with the pick-axe, twisting and turning it with his little hands and with all his might. Throughout, however, the smile on that thing’s face never faded.

The gnawing reality

The old man watched in horror as the boy tore apart his gut

Watching from the corridor and holding a lantern in his trembling hand was Madhu’s father. He stood petrified even as his young son, whom he always thought his bane, stared at the empty plate he had kept for his son and kept stabbing himself with the pick-axe.His innards hung from his torn guts and his mouth spewed out frothing blood. Then, turning suddenly and starting right into his eyes, the boy pleaded, ”Pattini anacha, korach kanji kittuo?(I am starving father, can I get some food),” before collapsing lifeless to the floor.

END